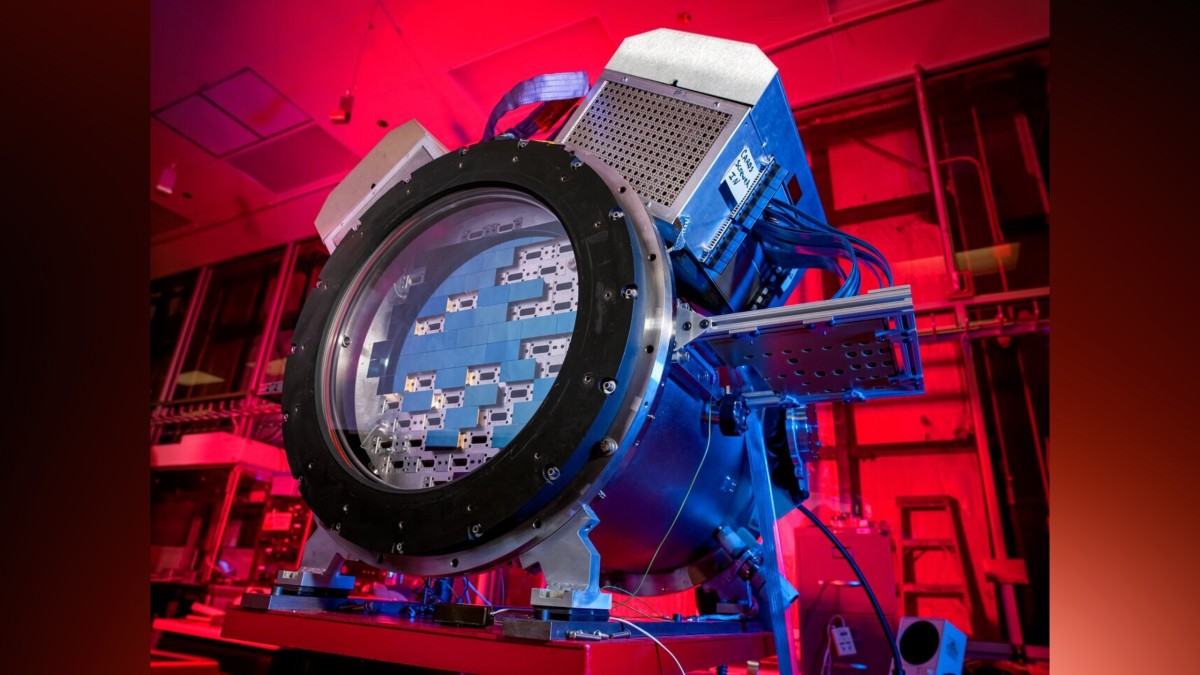

DECam is just one of the methods this study used to help reveal the nature of space itself.

Credit: DOE/FNAL/DECam/R. Hahn/CTIO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA

The Dark Energy Survey (DES) is in its sixth year of data collection, and the results continue to be useful to the quest to understand dark energy. The latest data release enabled researchers to combine four separate analysis methods to produce more precise results than previously possible. Together, they further constrain the possibilities for dark energy than ever before, strongly confirming what scientists know—and what they don’t.

Though things are still preliminary enough that the concept of dark energy could someday be overturned, most physicists still favor the idea that some kind of dark energy is real. Within this group, two basic theories compete to model dark energy: ΛCDM (Lambda cold dark matter) and wCDM.

DECam, used to collect much of the data used by the Dark Energy Survey.

Credit: Fermilab

The basic difference comes down to whether dark energy is an invariable constant or not. Each has different predictions for the large-scale evolution of the universe.

To check these predictions, the DES had to combine all four of the methods of investigating dark energy: study of signals from Type-Ia supernovae, optical investigation of the distribution of galaxies and galaxy clusters, looking at the universe through weak gravitational lensing, and mapping of the universe’s baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO).

In general, these are ways of looking at the current or past large-scale distribution of matter in the universe, and together they can help astronomers make incredibly precise calculations about the nature of dark energy. When the DES was first proposed 25 years ago, this sort of cross-checking was exactly what scientists were hoping for.

The team reports that while the results of all this searching do not preclude the wCDM model, they more strongly match the predictions of the ΛCDM model. The team found that their results constrain the possibilities for dark energy more than twice as strongly as past analyses.

However, their findings also confirmed and even expanded an existing problem with theory: the clustering of galaxies. Given readings of the early universe, both ΛCDM and wCDM predict a different pattern of galaxy clusters than is actually observed.

Of course, in astronomy, it’s always about quickly moving on to the next-next big thing. Most likely, that will involve incorporating imagery from the recently launched Vera C. Rubin Observatory. That monster can reconstruct images of tens of billions of galaxies, providing the most detailed insights yet into the large-scale structure of the universe.

In turn, that should provide even more specificity and further constrain the possibilities for dark energy. We’ll have to wait and see whether that sort of advancement will allow scientists to finally prove the nature of dark energy, or to understand the universe without the need for dark energy at all.