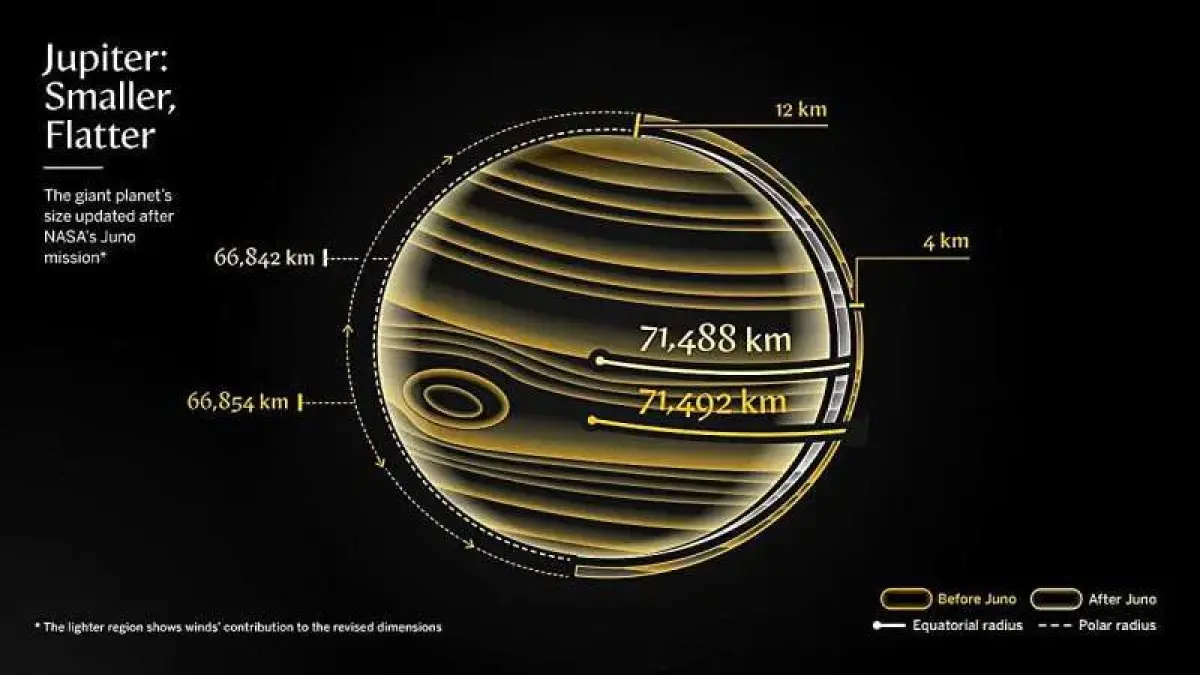

This illustration shows the difference between Jupiter’s older and newer measurements.

Credit: Weizmann Institute of Science

Astronomers with the Weizmann Institute of Science released newly precise measurements of the size and shape of Jupiter last week, revising its size slightly smaller and its shape slightly flatter. Despite Jupiter being one of the most prominent features of the night sky, first recorded in the 1600s, we still have lots to learn about our largest planetary neighbor.

The planet’s radius from pole to center has been revised to 66,842 km, and at the equator to 71,488 km. That makes it about 12 km smaller along the poles, and about 4 km smaller at the equator, than previously believed. The data were collected by the Juno spacecraft still in orbit around Jupiter.

Even such a small change can help understand the internal dynamics of the planet, and help validate other observations like its atmospheric composition.

“Textbooks will need to be updated,” said Weizmann’s Yohai Kaspi.

Much smaller, and they’ll have to start calling it the Pretty Good Red Spot.

Credit: NASA

Still, though, there is the question of why astronomers are still figuring out the size and shape of such a large, nearby object?

The main reason is that we can’t do, from Earth, what a far-away probe can do from orbit: shoot out radiation from nearby to the planet in question.

With hard planets, this can allow bouncing of radio waves off the surface, for collection and analysis; with the less reflective “surfaces” of gas giants, the tactic has instead been to shoot radio waves back towards Earth, from beside the planet. Neither of these things can be replicated from Earth, since no technology could generate a strong enough signal to get all the way to a distant planet, bounce off its surface, and return for analysis.

Without that, terrestrial science is limited to viewing distant planets with telescopes only, and that has inherent disadvantages.

For one, telescopes can only measure a planet by measuring the distance from one visible edge to another, which is made difficult by the fact that atmospheres make these edges unavoidable fuzzy. That applies both to thin-atmosphere planets like Mars and thick-atmosphere gas giants like Jupiter.

More than that, though, even large and nearby planets are relatively small and far away, meaning that even powerful telescopes have a hard time with ultra-precise measurements. When viewed from Earth, Jupiter is an average of about 40 arc-seconds wide; on the Hubble telescope, which has about a 0.05 arc-second resolution, this would make Jupiter about 800 “resolution elements” across.

A render of the Juno spacecraft.

Credit: NASA

That’s a nice number of elements for resolving beautiful, high-definition images for publication but it actually only allows estimation of the planet’s size down to the level of a few kilometers. To get to meter-level precision, you need to get right up close.

The Juno mission performed its measurements by receiving radio waves from Earth and then shooting them back for analysis. Specifically, it uses the Deep Space Network (DSN) to measure the return time-of-flight of these transmissions, and so measure strength of the gravitational field around the probe.

By mapping this field over many measurements, the probe can discern the planet’s size with extreme accuracy. Previous probes from the Voyager and Pioneer missions have taken similar measurements, but only six; Juno increased the accuracy of Jupiter’s sizing by adding a couple of dozen more such readings, of its own.

To take this even further, this team also took advantage of a unique opportunity to communicate with Juno as it passed behind Jupiter, from Earth’s perspective. The signal bent, slightly, as the probe disappeared behind the planet’s enormous mass, and this deflection allowed even more precise calculation of the strength of the planet’s gravitational field.

As astronomers continue to invent new and elaborate ways of detecting exoplanets and exotic black holes, this week’s news is a reminder that, in science, even the fundamentals are always under investigation.